Sam Roots, Experience & Interaction Designer, Royal College of Art & Imperial College London

Using design to change our spending behaviour

Back in the days of cash-only transactions, it was easier to keep control of your money: if you didn’t have it, you couldn’t spend it. That direct physical link to our money also gave us a strong sense of when, and how much, we were spending. Today the picture is a bit different. From contactless cards, to one-click order buttons, to emails reminding you that you have items in your shopping basket – we live our lives through a series of designed experiences controlled by others. Because it’s so easy to spend, our rational intentions can be easily crowded out by the emotional factors. The idea of ‘self-control’ has become almost revolutionary: the option of not consuming is practically taboo, and it’s sometimes hard to remember it even exists.

This disproportionately affects people with mental health problems. But thanks to organisations like Money and Mental Health, it’s now possible to have serious conversations about designing products that take this into account.

Speed bumps for spending

Some have talked about introducing ‘friction’ – tweaking the interface to make ‘unhealthy behaviours’ harder – but this is difficult to do. Make something too difficult to use, or too paternalistic, and you risk annoying and alienating your users. Make it too easy, and the friction has no effect. In a market where competitors are often distinguished by how user-friendly they are, companies may also find it hard to justify making a product harder to use.

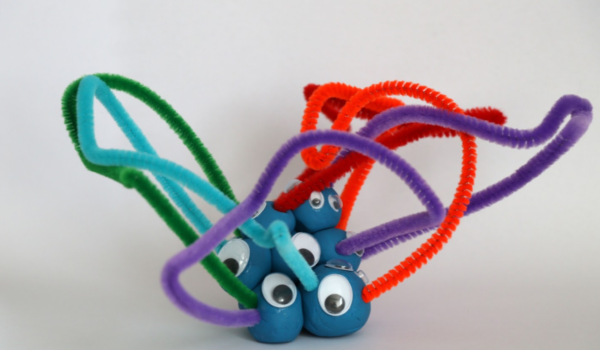

To be a designer faced with these kinds of complex problems, it’s hard to know where to begin. The key – of course – is to work with your users and let the design be informed by their needs. For the past five months, I’ve worked with people who have experienced periods of emotionally-driven spending, and in some cases manic extravagance, to understand how their experience of money could be transformed. Using a range of serious and playful techniques to do this – from asking participants to fill out diaries of mood and spending, to inviting them to create a monster from plasticine and pipe-cleaners, that represented their relationship with money (and to explain it!).

Through several rounds of user research and feedback, I created a product called Treasure to support a healthier relationship with money and spending. Treasure is a system that acts like a protective layer around your finances, putting control of the user experience back in the user’s hands. Treasure is currently only a prototype, but I’ve already had some fantastic feedback and I hope to continue developing it.

Treasure

Treasure basically does two things. First, it introduces a voluntary ‘friction’ at the point of payment, in the form of a very simple puzzle on a physical device – when you want to make a payment, you have to confirm it by pressing a random three buttons that light up. Without needing to memorise any codes, this forces the user’s attention away from their devices for a second. It prompts a moment of reflection.

One of the key aspects of Treasure is that it should respect the freedom of the user while still holding them accountable. If they really, really want to spend their money, they are still able to – but Treasure helps make the decision more obvious and reflective.

The second function of Treasure is to support a healthier relationship with money more broadly, through accountability. It does this with an app that promotes greater engagement with the user’s finances. For example, it prompts the user to reflect on a few of the previous day’s expenses, asking if they are still happy with them. It helps them make financial plans, and to stick to them. Over time, it gives the user insights into their own behaviour, helping them recognise their triggers – and alert them when they might be more likely to impulse-spend. The physical friction then also becomes a shorthand prompt – “Am I OK making this purchase?”

Treasure won’t work for everyone, in every situation – users must buy into it voluntarily, and those with much more serious money control problems (like uncontrolled spending in a manic episode) would likely need more than just a greater sense of accountability. My hunch is that products like this will factor in layers of social support in future too. But these are still early days, and this is a vast topic.

I look forward to seeing where we can take it together.