Nikki Bond, Research Assistant, Money and Mental Health

Too ill to work, too broke not to

01 November 2018

It has been exactly one year since the publication of Thriving at work: the Stevenson / Farmer review of mental health and employers, which outlined the necessity for workplaces to support people experiencing mental health problems. A key recommendation was for the government to introduce a more flexible model of sick pay.

This recommendation chimed with messages from our Research Community, who shared their experience of the impossible dilemma of being too unwell to work, while simultaneously being unable to afford to take time off to recover.

Today we’re pleased to be launching our new report, ‘Too ill to work, too broke not to, which explores this predicament, and the devastating financial consequences of sickness absence for people experiencing mental health problems.

The adequacy of replacement incomes

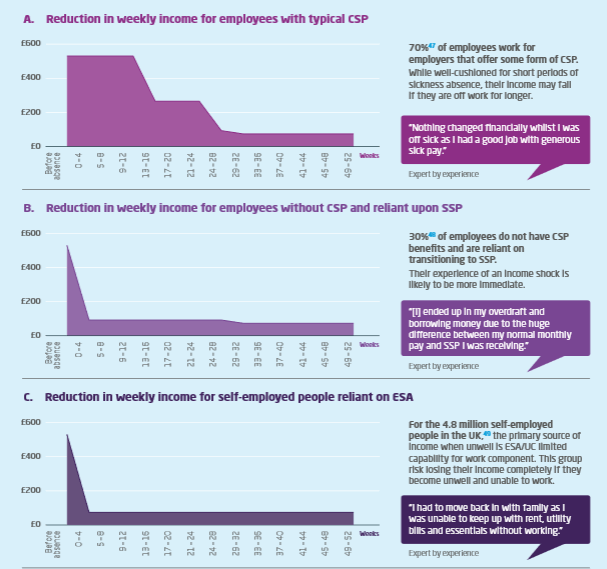

When people are too unwell to work, state or employer sickness benefits provide a financial safety net. Some employees benefit from some form of contractual sick pay, but if their illness is severe or their recovery protracted, these sickness benefits often run out – leaving people reliant on the significantly reduced income of statutory sick pay.

For other people who do not benefit from contractual sick pay (CSP) or are self-employed, their journey to financial difficulty is swifter, moving suddenly from full pay to statutory sick pay (SSP) or employment support allowance (ESA). As the diagrams below show, these income reductions can be crippling.

Prolonging recovery

Mental health problems can impact a person’s ability to think clearly, retain information, plan and problem solve – all skills required for financial management and budgeting. As a result, people are faced with managing these stark income reductions when they are least able to do so.

For many physical health problems, we have an idea of how long recovery will take: a cold – a few days off; a fractured leg – six weeks of recovery. While these timescales are only rules of thumb, they help to guide a person in budgeting and figuring out how to manage financially while they’re unable to work.

But recovery trajectories for mental health problems are often more complex. Recovery rates depend upon responses to medication, access to counselling services, and personal circumstances of reduced stress to allow a person to focus on their mental health.

If a person is constantly worrying about making ends meet, not being able to pay the rent, put food on the table, or feed the electric meter – this environment of worry and fear is not conducive to recovery. In fact, it can exacerbate mental health problems, and ultimately delay someone’s return to work.

A more flexible approach

Workplace sickness absence is currently viewed rigidly – with the assumption that people are either well enough to work or they are not. This simply does not accurately reflect the nature of mental health problems. For some, a period of full-time sickness absence is absolutely required, while others may be well enough to do some work, but perhaps need additional support or reduced hours.

We are calling for government to increase the flexibility of Statutory Sick Pay, by allowing people to combine wages and sickness benefit – both as an alternative to full-time sickness absence and as a supportive mechanism following periods of full-time absence.

This would support individuals by reducing the financial devastation caused by sickness absence, while also benefiting employers by avoiding the costly resource and productivity implications of people trying to perform their normal roles and working hours while too unwell to do so.

Given that a person who has been off work for six months or more has an 80% chance of being off work for five years – and that 300,000 people with a long-term mental health problem lose their job each year – a more flexible approach to sickness absence is much-needed. It could go a long way in breaking the cycle of people being too ill to work, but too broke not to.