Conor D’Arcy, Interim Chief Executive, Money and Mental Health Policy Institute

The government’s new Suicide Prevention Strategy: bold action is needed

11 September 2023

Please note: this page/post contains information about suicide that readers may find distressing. If you’re in need of support, you can call Samaritans for free on 116 123 anytime of the day – or you can text SHOUT to 85258. For information about where to find support with your money or mental health, you can find some resources on our get help page.

- The updated Suicide Prevention Strategy for England was published today.

- We are pleased to see that the strategy recognises the link between financial difficulty and suicide.

- Rising living costs in recent times have contributed to an increase in suicidal thoughts and feelings, particularly among people who are behind on multiple payments.

- Honest, bold action is needed to protect individuals experiencing financial hardship, including a review of benefit deductions’ impact on mental health.

The publication this morning of the updated Suicide Prevention Strategy for England is an important moment. It gives us a chance to reflect on what’s changed and what’s been achieved since the last version was published back in 2012. But with any strategy, what really matters is what it says about the world today, and what needs to be done to reduce the number of people dying by suicide.

A welcome new focus on financial difficulty

From a Money and Mental Health perspective, the biggest – and most welcome – development in this update is the recognition that financial difficulty and economic adversity are risk factors linked to suicide. Back in 2012, the strategy made only a few references to how people’s economic circumstances could place them at higher risk of suicide. In the new strategy, and the action plan published alongside it, these issues form a much more central part of the diagnosis of how things stand today and where attention is needed.

That shift in emphasis is vital and represents a growing awareness we’ve seen since we started working on these issues in 2016. We regularly speak to stakeholders across so many different sectors: banks, energy firms, government departments, regulators, debt advice and healthcare, including mental health.

While there is still much that needs to be done, the toxic cycle that money and mental health can form is becoming more and more understood across these diverse industries. If this strategy hadn’t put financial difficulty front and centre, it would have felt out of step with where policy and practice have increasingly been moving.

Where we are today

But, unfortunately, another reason why the links between suicide and financial difficulty are so apparent today is the toll the cost of living has taken over the past 18 months or so. Indeed, the strategy points to some of the work we’ve done on this topic. In our first paper on the psychological impact of keeping up with rapidly rising prices, a worrying number of our Research Community – a group of 5,000 people with lived experience of mental health problems – told us just how difficult things had been.

“I have removed any little luxuries that I used to enjoy and will now only have the heating on for 3 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the evening, despite being at home nearly all day, everyday. When I get cold, I go to bed and stay there. This does nothing for my mental health except make me feel even more depressed and suicidal.” Expert by experience

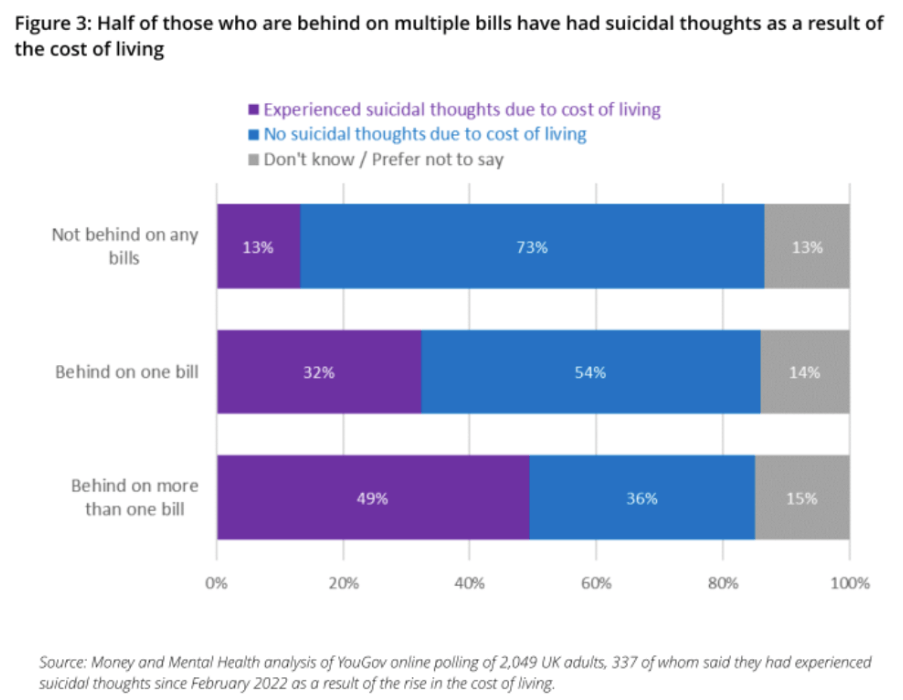

When we published our second paper on the topic, we commissioned polling to get a more representative picture of the national experience. Suicide is a complicated topic, so we’re always cautious about over-interpreting the responses to a single question. But in polling we first conducted in November 2022, we found that one in six (17%) said that they had experienced suicidal thoughts or feelings as a result of the rise in the cost of living. We repeated that question again in June this year and found it virtually unchanged at 18%. Most worryingly, that share rose to half (49%) of those who were behind on more than one kind of payment like energy bills or rent.

Moving from emphasis to action

Against that backdrop, a renewed focus on suicide prevention is crucial. But when we speak to all those different stakeholders, it’s clear there isn’t a single answer to break the link between financial difficulty and suicide. That’s why the strategy’s breadth is essential.

It’s right that the strategy sets out a central role for the health system in reducing suicides, but I’m pleased to also see a spotlight shone on two key parts of how government interacts with people. With people behind on payments more likely to say they have had suicidal thoughts, it’s helpful that how government itself manages debt – for instance benefit overpayments or through HMRC – is given attention. The action plan commits to considering how support and training for people in frontline services can be strengthened. This is positive, but in a project we’ll be launching later this year, we’ll be looking at whether there’s more fundamental steps that government (as well as other creditors) could take to protect people who’ve fallen behind.

The Department for Work and Pensions is the other part of government given specific attention. An action point for it relates to work to “identify opportunities” to review and strengthen existing guidance for people experiencing suicidal thoughts or feelings. As a research charity, we’d never discourage any organisation from being thoughtful about their approach and drawing on evidence. But making sure the resources are in place so that work can be completed quickly, and the steps taken afterwards is vital. Based on what we hear from our Research Community, it’s likely to throw up some difficult questions for the DWP, for instance how deductions to benefits are applied and the impact they have. If the government is serious about reducing suicide, being honest and bold will be needed.