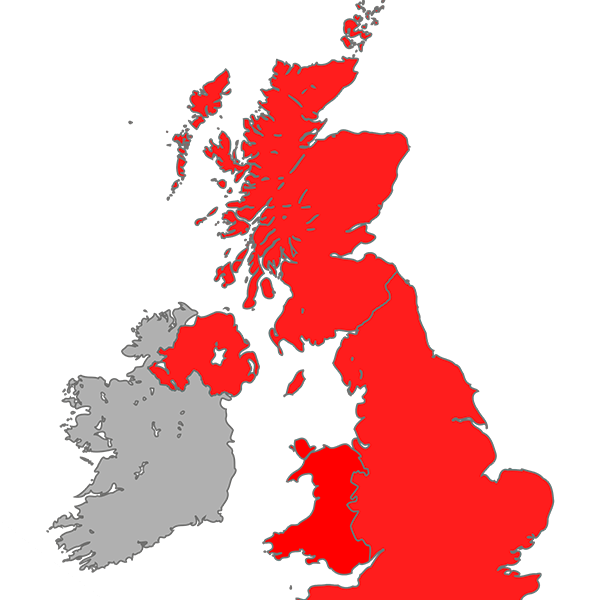

Britain in the red

Why debt problems aren’t always caused by ‘problem debt’

The TUC recently grabbed the headlines with a warning that 1.6m families were living in extreme debt. Underpinning those headlines was a detailed and complex report looking at how we can improve our understanding of households’ debts – and how well they are coping with them.

Money and Mental Health’s work – and that of others – has shown that debt problems are closely linked to mental health problems. The more debts a person has, the more likely they are to have a mental health problem.

The TUC’s report exposes some interesting phenomena about people’s feelings about their debts that we will explore more in our ongoing work. These phenomena demonstrate how important it is to consider more than just the numbers when trying to understand the impact of debt in our society and economy.

Underestimating how much we owe

First – we know it’s hard to estimate accurately the total amount of UK indebtedness, but it seems individuals and families struggle just as much to estimate their own level of personal debt. The TUC find that when asked about the value of their debt, people seem to be underestimating: total debt figures from self-reported household surveys are – systematically – much lower than the total debt figures from aggregate data.

Why is this happening? One major reason could be that family members don’t tell each other about all the debts they have taken on. This is cause for concern: secrecy about financial problems can lead to relationship difficulties, and subsequent relationship breakdown – worsening both financial and mental health problems.

Second – the impact of debt on households seems to vary dramatically. You might expect it to be closely linked to the size of people’s debts, or at least their debt to income ratio. But the TUC finds that people’s ability to service the debt and whether they view it as a ‘heavy burden’ in their lives do not simply correlate.

Why small debts can cause big problems

Less than a quarter of extremely over-indebted households reported that their debts were a heavy burden, while a tenth of households with very low levels of debt felt that their debts were a heavy burden. For me, that’s a salient reminder of the importance of understanding people’s feelings, and the details of their individual circumstances, before we start classifying what kind of debts are a problem.

In total, more people reported their debts to be a heavy burden than were technically classed as ‘over-indebted.’ This serves as a useful reminder that a technical measure of indebtedness does not reflect the potential impact on people’s lives. It is not just people with ‘extreme problem debt’ that may suffer an impact on their mental health, the impact can be much wider.

Understanding how debt affects wellbeing

It is of course useful for the purposes of macroeconomic risk assessments to understand in simple terms which debts are likely to be paid, and which fall into arrears. But if we want to understand the impact on people’s wellbeing, we need to be more creative.

That’s particularly true when it comes to ‘bad’ debt that’s been written off by primary creditors. The TUC points out that once this debt has been written off, it is no longer included in calculations of consumer debt. But if a debt has been sold on to a debt purchase company, the individual debtor remains liable, and can be pursued for the full amount. The secondary market for debt is growing, and continues to do so. £900m was collected in 2014 alone.

But while the Bank of England disregards these ‘bad’ debts for its economic assessments, the pursuit of payment can have a profound and life-limiting impact on individual families, including on the wellbeing of children and dependent relatives. When people’s mental health takes a turn for the worse, it can affect their ability to work, to manage their budget, to deal with creditors, and to care for their family. So it’s in the interests of the whole credit collections industry to work sensitively with those at risk of, or experiencing, a mental health problem.