Conor D’Arcy, Head of Research and Policy, Money and Mental Health

New ONS data highlights mental health living standards inequalities

19 February 2021

The disruption of the past year has shone a light on longstanding inequalities across society. A new batch of data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) provides new insight on outcomes for one often disadvantaged group: people with disabilities, including those with mental health problems. Much of the data finishes in mid-2020, so while it may reflect some of the effects of the pandemic, what’s more notable are the entrenched differences it reveals (you can read the ONS data here).

Definitions are important

Focusing in on people with mental health problems, however, raises some questions before we even get to the results. The kinds of conditions that are commonly grouped as relating to mental health are mostly split into two categories: people with “depression, bad nerves or anxiety” and people with “mental illness or other nervous disorders”. These options have been used in key surveys for years, and statisticians are always reluctant to tweak the wording of questions and answers as it limits what you can say about change over time. Iif the percentage of people answering a certain way jumps the following year, was it due to the new phrasing or a ‘real’ shift?

But when it comes to an issue like mental health, where huge progress has been made in medical and wider public understanding in recent years, there is a strong case for updating vague and outdated terminology like “bad nerves”. And while trade-offs will always have to be made on the number of options provided in a survey, bundling up nervous disorders which could include conditions like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s with mental illness like schizophrenia risks concealing more than it reveals, with their differing needs and challenges.

The mental health employment gap

Despite this, the data still provides a valuable insight into how people with mental health problems are faring when it comes to living standards – from employment, education and housing.

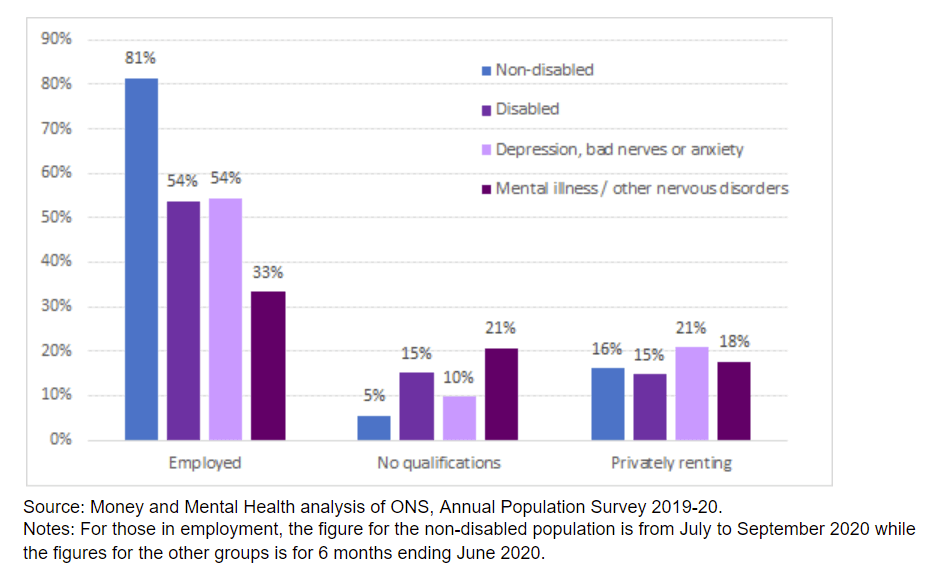

In particular, the new data highlights the challenge that people with mental health problems are facing in accessing employment. While four in five (81%) working-age people without a disability were in work, that dropped to just over half (54%) of people with depression or anxiety. Just one in three (33%) people experiencing mental illness or a nervous disorder were employed. As our Mental Health and Income Commission found, for some people with mental health problems, their health is likely to make remaining in work a challenge. But many of our Research Community told us how they were keen to have a job but that inflexibility, a lack of knowledge and discrimination could all make that harder. The Commission’s final report and our best practice checklist for employers set out how this employment gap could be narrowed. Read the full checklist for employers here.

Outcomes for people by disability

Education and housing

Alongside the employment gap, the data also reveals some other interesting differences between people with and without disabilities. As a group, people with disabilities are more likely to have no formal educational qualifications compared to those with no disabilities (15% versus 5% respectively). That figure is even higher – 21% – for people experiencing mental illness or other nervous disorders.

Education can be fulfilling in itself but also tends to open up more employment opportunities. While these conditions can make it harder to complete qualifications — and age and other considerations may play a role — these differences nonetheless raise concerning questions on how accessible educational systems are for people with mental health problems.

Differences in housing are less stark than in employment and education but point to issues which may be of growing concern in the months ahead. People with depression or anxiety and those with a mental illness or nervous disorder appear a little more likely to be renting privately. While age may be a factor in this, with younger people for instance more likely to be renters, the insecurity that renting privately can bring can be difficult to manage.

With the pause on home repossessions by bailiffs currently set to come to an end in April, people who have faced an income drop may be faced with losing their home. Factoring in the impact on people’s mental health of such action – both for people with existing mental health problems and those who understandably will be affected by it – should be a key consideration for government when it considers whether to extend the pause.