Georgia Preece, Research Assistant, Money and Mental Health

Mental health and the pandemic: What do the latest ONS stats tell us?

17 June 2021

So many of us have personal experience of the negative mental health impact of the pandemic, but what does the impact look like on a societal level? The Office for National Statistics’ most recent stats surrounding rates of depression in the UK and diagnosis of depression by GPs in England can give us some insight. The data shows the detrimental effect of the pandemic on people’s health and wellbeing, as well as highlighting the unequal impact of the pandemic on people’s mental health – a factor that can’t be ignored when building back from the pandemic.

Prior to the pandemic, rates of depression in the UK were around 10% of the general population. Now, they have over doubled to 21%, rising slightly from November 2020. It’s hardly surprising that rates of depression have increased across the UK; with 8.9 million furloughed, people unable to spend as much time on hobby activities and many isolated from family and friends.

The unequal impact of the pandemic

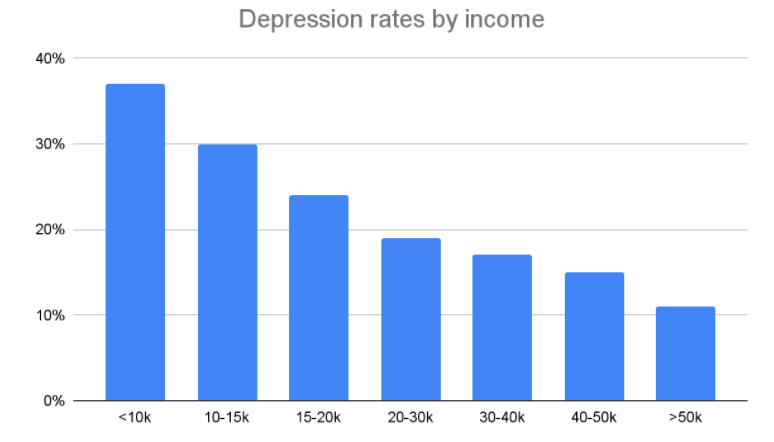

The data also shows that the pandemic has not affected everyone equally. Rates of depression were highest amongst younger people, disabled people and those who were clinically extremely vulnerable. As shown in the graph below, those who are unemployed and on incomes less than £10,000 were shown to experience higher rates of depression; with those on less than £10,000 over 3 times more likely to experience depressive symptoms. When on a lower income, we cannot always be prepared for financial shocks like the Covid pandemic, whether that’s from a reduction in working hours or increased utility and food bills from spending more time at home.

Source: Office for National Statistics – Opinions and Lifestyles Survey

The data has also highlighted the geographical disparity in mental health, with higher rates of depression in Yorkshire and the Humber, and London. The North East of England has been disproportionately affected by Covid in the last year, both by death rates (an extra 57.7 people per 100,000 died compared to the rest of England between March and July), mental wellbeing and economic hardship. 28% of those in the most deprived areas of the UK reported experiencing depressive symptoms. We know that the pandemic has disproportionately affected some communities and demographic groups and this needs to be taken into account going forward.

Rates of diagnosis and accessing care

Moving beyond the geographical impact, Covid has had an unequal impact on society. Our past research shows that only 1 in 3 people with mental health problems have received a diagnosis. The pandemic has potentially widened this gap, with diagnoses of depression by GPs having gone down. This is likely because people haven’t gone to their GP during the pandemic, or haven’t been able to access appointments.

While the number of mental health diagnoses has gone down, they make up a higher proportion of all new health diagnoses, signalling that people are not accessing healthcare at a normal rate, and potentially flags issues surrounding digital exclusion. This also contrasts with the increase in self reported feelings of depression in the UK during the pandemic. Previous data has also shown that 1 in 5 people who have had Covid go on to develop a mental health problem like depression or anxiety, and so presents an increased long-term need for mental health services that adequately cater to peoples’ specific needs.

The impact of Covid has been devastating for many, and we’re not out of the woods yet. As we recover from the pandemic, policymakers will need to take into account the long term impact on mental health, and recognise that unemployment is likely to rise as the furlough scheme ends. Our previous research has established a clear link between financial problems and mental health problems, and so it’s important that people can access services that they need (like doctors, support services and diagnoses) as well as being able to get by financially.