Polly Mackenzie, Director, Money and Mental Health

Is Facebook tipping-off advertisers about your mental health?

Most of us spend more when we’re feeling low. Whether it’s a pick-me-up shopping trip, a takeaway when we can’t face cooking, or trying to escape through the bottom of a pint glass, we’ve all been there, and paid the bills afterwards. That’s why news that Facebook may have been giving retailers and advertisers an insight into the mood of its users – including children as young as 14 – is deeply concerning.

The Sun reported yesterday on a leaked internal document setting out how marketers could track when people were feeling ‘overwhelmed’, ‘worthless’ or ‘insecure’. I haven’t seen this internal document, and Facebook says the intention was merely to help marketers understand how people express themselves, not allow them to target their adverts. But there’s a huge risk here, so it’s right to ring a huge alarm bell.

Retailers might very well want to know when people are feeling worthless or insecure: because when we’re down, our defences are down too. We’re vulnerable, and in particular we’re vulnerable to the misguided promise that stuff will make us feel better. But just like overeating or self-harm, our research shows that these kinds of purchases simply don’t work: people might feel better briefly, but then they fall into a cycle of blame and self-recrimination that simply makes them feel worse.

Creating the echo-chamber

Writing in the Guardian today, a former Facebook exec says:

‘Who cares? Data simply reflects reality. Why does it matter if poor, urban black consumers get pushed adverts for payday loans, and middle class, white women see only adverts for expensive athleisure wear? These are the right audiences for those products – the people most likely to buy.’

But it is not that simple. The environment in which we live shapes the decisions we make in a profound way. High streets in poor communities can be toxic: payday lenders, gambling and fried chicken dominate. We are now creating online environments that similarly reinforce patterns of damaging behaviour. It matters if poor consumers see the most payday loan adverts because it changes their behaviour, reinforces the data stereotype that feeds them the adverts, and compounds social division.

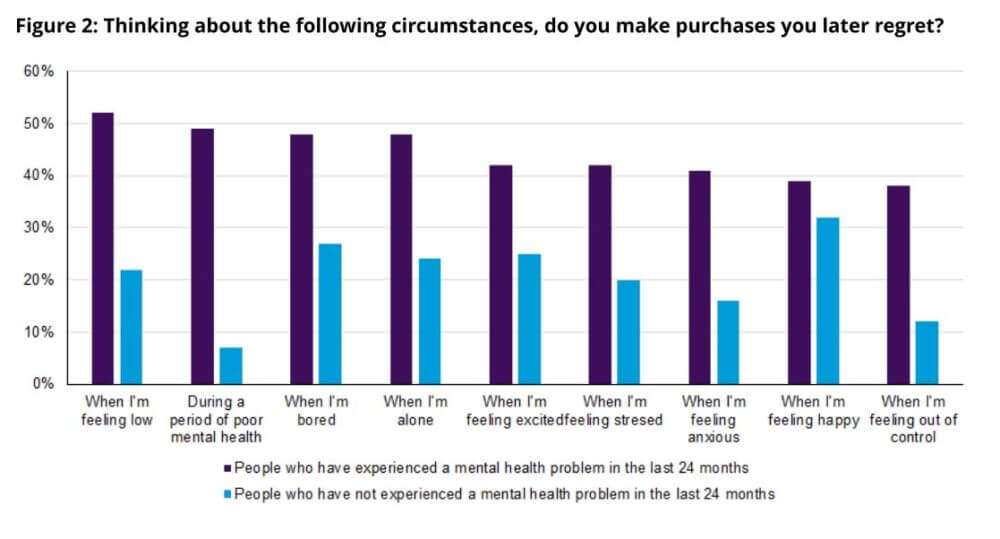

Our always-on shopping environment – reinforced by incessant marketing – makes it incredibly easy to make mistakes. Polling work we did for a recent project on responsible retailing shows quite how important mood is when it comes to making mistakes. The graph below shows the times people bought something online that they later regretted. It shows we all make more mistakes when our mood is off-balance – but especially those of us with a history of mental health problems.

A moral decision

I look at this table and wonder how best to protect people from making expensive mistakes when they’re vulnerable. But from a marketing perspective, these people aren’t vulnerable – they’re responsive. A marketer might think: these are the moods when people are most likely to click through to purchase, so these are the moods I want to target with my ads. In some ways it’s no surprise that retailers want to sell their goods – it’s what they’re in business for. But any retailer looking for ways to get at people whose defences are down needs to take a long, hard look at their moral code.

There’s an increasing body of research on what’s called “sentiment analysis”: filtering people’s social media feeds looking for indicators of mood. From the colour of your photographs to your use of capital letters, there’s an academic somewhere who’s run a big data project on it. It’s fascinating stuff, but this knowledge has immense power to do us harm. The guardians of our online spaces – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and more – need to take responsibility for the advertising they expose us to, especially when we’re vulnerable.

It’s inevitable that these big companies will know a huge amount about us, including those awful moments when we’re feeling worthless, or insecure. That knowledge must not be used to prey on us, and sell us the lie that a box of beauty products or a bet on the upcoming football match will lift our mood. If it’s to be used at all, it should be used to lift our spirits with what actually works: links to help and support, connections with our family or our friends, and tools to help get through the tough times without wasting money you can ill afford.

Find out more – read our policy note on night-time shopping and targeted marketing.